The て-form of a verb + いる is commonly used to express ongoing actions. For example:

- 「食べています。」(たべています) — “I’m eating.”

- 「聞いています。」(きいています) — “I’m listening.”

So, when you’re on your way to meet a friend and want to let them know, you might think it’s natural to say:

「行っています。」(いっています)

However, this is a very common mistake for Japanese learners.

「行っています」(いっています) does not mean “I’m heading there now.”

When it comes to the verb 行く (いく), understanding its nuances is crucial to avoid misunderstandings.

Understanding the Usage of 行く(いく) and Related Expressions

行く (いく)

- To go (used for actions planned for the future or habitual actions).

行っている (いっている)

- To commute (regularly go somewhere).

- To currently be at a location (having arrived there already).

⚠️ 行っている does NOT mean “heading to your destination.”

向かっている (むかっている)

- To head towards a destination.

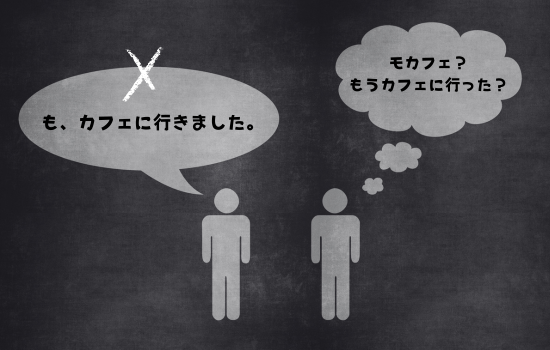

Incorrect Example

Dialogue:

A: 「駅に着いたよ。」(えきに ついたよ。)

B: 「今、行ってるよ。」(いま、いってるよ。)

A: 「え?どこに?」

A: “I’ve arrived at the station.”

B: “I’m going now.”

A: “Huh? To where?”

Explanation:

Here, B’s response is unnatural because 「行ってるよ 」(いってるよ) sounds like B is heading somewhere, but not to A’s location (the station). This causes confusion, as A expects B to confirm they are coming to the station, not somewhere else. The correct phrase to use here would be 「今向かってるよ」(いま、むかってるよ) to indicate that B is specifically on the way to meet A.

Correct Example

Dialogue:

A: 「駅に着いたよ。」(えきに ついたよ。)

B: 「今、向かってるよ。」(いま、むかってるよ。)

A: 「オッケー!」

A: “I’ve arrived at the station.”

B: “I’m heading there now.”

A: “Ok!

Explanation:

Using 「向かってる」(むかってる) clearly conveys that B is on their way to the station. It avoids the misunderstanding caused by 「行ってるよ」(いってるよ) in this context.

Correct Example (Meaning: “Commute”)

Dialogue:

A: 「ヨガ始めたの?」(よが はじめたの?)

B: 「うん。毎週行ってるよ。」(うん。まいしゅう いってるよ。)

A: “You started yoga?”

B: “Yeah, I go there every week.”

Explanation:

In this context, 「行ってる」(いってる) refers to a habitual action — regularly going to a yoga class. It’s the correct usage for expressing this idea.

Correct Example (Meaning: “Currently Visiting”)

Dialogue:

A: 「山本さんは?」(やまもとさんは?)

B: 「山本さんは今、クライアントのところに行っています。」(やまもとさんは いま くらいあんとの ところに いっています。)

A: “Where’s Mr. Yamamoto?”

B: “Mr. Yamamoto is currently at the client’s place.”

Explanation:

Here, 「行っています」(いっています) means that Mr. Yamamoto has gone to the client’s location and is currently there. It does not mean he is on his way.

Additional Examples (Currently Visiting)

- Dialogue:

A: 「田中さんは?」(たなかさんは?)

B: 「田中さんは出張で北海道に行っています。」(たなかさんは しゅっちょうで ほっかいどうに いっています。)

A: “Where’s Mr. Tanaka?”

B: “Mr. Tanaka is currently on a business trip to Hokkaido.”

Explanation:

This sentence means that Mr. Tanaka has already traveled to Hokkaido for a business trip and is presently there. - Dialogue:

A: 「林さんは?」(はやしさんは?)

B: 「林さんは今、休暇でハワイに行っていますよ。」(はやしさんは いま きゅうかで はわいに いっていますよ。)

A: “Where’s Mr. Hayashi?”

B: “Mr. Hayashi is currently on vacation in Hawaii.”

Explanation:

Again, this indicates that Mr. Hayashi is already in Hawaii for his vacation.

Other examples sentences

1. 子供の頃はよく祖父母の住んでいる田舎に行っていました。

(こどものころは よく そふぼの すんでいる いなかに いっていました。)

ー”When I was a child, I often visited the countryside where my grandparents lived.”

Explanation:

「行っていました」(いっていました) is used here to describe a habitual action in the past, indicating the speaker often visited their grandparents’ home during childhood.

2. 大学生の時は冬になると友達とスノボに行っていました。

(だいがくせいのときは ふゆになると ともだちと すのぼに いっていました。)

ー”When I was a university student, I used to go snowboarding with friends every winter.”

Explanation:

This sentence uses 「行っていました」(いっていました) to describe a repeated activity during the speaker’s university years.

3. 小学生の時、スイミング教室に行っていました。

(しょうがくせいのとき、すいみんぐきょうしつに いっていました。)

ー”When I was an elementary school student, I used to go to swimming lessons.”

Explanation:

Here, 「行っていました」(いっていました) expresses a habitual activity in the speaker’s past, specifically attending swimming lessons regularly.

4. 今そっちに向かってるんだけど、バスが遅れてて、10分以上遅れそうなんだ。ごめんね。

(いま そっちに むかってるんだけど、ばすが おくれてて、じゅっぷん いじょう おくれそうなんだ。ごめんね。)

ー”I’m heading there now, but the bus is running late. I’ll probably be more than 10 minutes late. Sorry!”

Explanation:

「向かってる」(むかってる) is used to indicate that the speaker is currently on their way to the destination but is experiencing a delay.

5. 今、クライアントのところに向かっています。5分ぐらいで着きます。

(いま、くらいあんとの ところに むかっています。ごふん ぐらいで つきます。)

ー”I’m on my way to the client’s office. I’ll arrive in about five minutes.”

Explanation:

「向かっています」(むかっています) communicates that the speaker is currently heading to the client’s office, with an estimated arrival time included for clarity.

6. 今、スーパーに向かってるんだけど、何か欲しいものある?

(いま、すーぱーに むかってるんだけど、なにか ほしいもの ある?)

ー”I’m heading to the supermarket right now. Do you want me to get you anything?”

Explanation:

Using 「向かってる」(むかってる) indicates that the speaker is in the process of going to the supermarket, while the follow-up question makes the situation interactive.

7. キャンプ場に向かってたら、突然ひどい雨が降り出して、行くのをやめたよ。

(きゃんぷじょうに むかってたら、とつぜん ひどい あめが ふりだして、いくのを やめたよ。)

ー”I was heading to the campsite, but it suddenly started raining heavily, so I decided not to go.”

Explanation:

「向かってたら」(むかってたら) describes the speaker’s action of heading toward the campsite, which was interrupted by the sudden downpour. The decision to stop going is explained as a result.

Conclusion

Context matters. Be careful to choose the right expression to avoid confusion!

「行っています」(いっています) is often misunderstood by learners to mean “heading somewhere.” Instead, it refers to habitual actions or the state of being at a place.

Use 「向かっている」(むかっている) when you want to say you’re on your way to a destination.